I have recently written a paper where I estimate global glacier volume to be 35 cm using a statistical approach .

The statistical approach i use is a refinement of volume-area scaling where I include additional predictors of volume. These are elevation range (R), glacier length (L), and Continentality (C). The statistical approach I use is simply multiple linear regression in log space. I thus fit relationships of the form: V=k_Aγ1_Rγ2_Lγ3_Cγ4.

Recent estimates of global glacier volume:

Grinsted 201335 cm +/- 7 cm Huss & Farinotti 201243 cm +/- 6 cm Radic & Hock 201060 cm +/- 7 cm Radic & Hock 2010 applied to RGIv2*

~50 cmA more complete history is given in Cogley 2012.

(*) I have seen two different updated RH10 estimates from presentations by Hock and Huss and they both were just around 50cm but about 5 cm different.

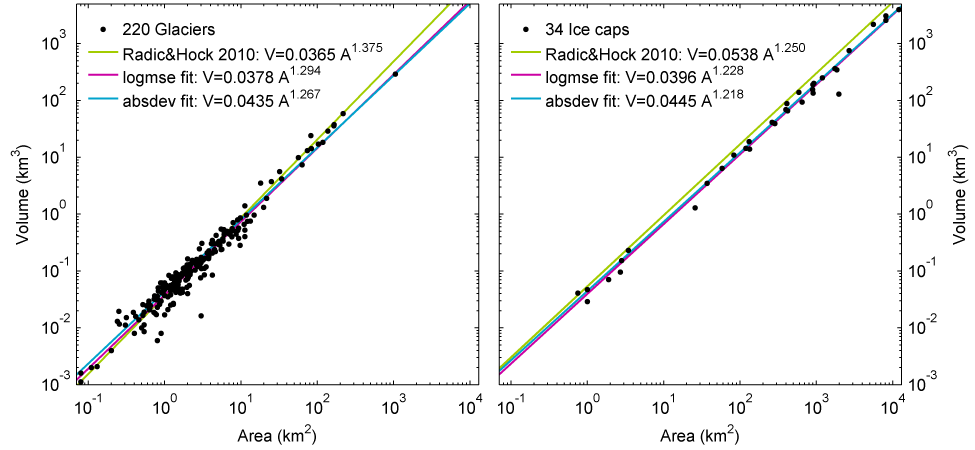

My estimate of 35 cm is below Radic & Hock’s 2010 estimate even when RH10 is updated to use the new RGIv2 inventory. Both estimates are scaling based, and the reason for the difference must be found in the applied volume-area scaling relationships. The figure below show that there is a clear positive bias in the Radic & Hock 2010 ice cap relationship. It is less obvious for the glacier relationship. However, when the Radic and Hock 2010 relationship is applied to the 220 glaciers and 34 ice caps in this sample then both relationships result in 40-50% too great a total volume. One key difference between my study and Radic and Hock (2010), is that I calibrate the scaling law myself whereas they use published scaling relationships. These published relationships were calculated using a smaller subset of the glacier volume data than was available to me. It will be interesting to see what happens as the database of glacier volume estimates grows.

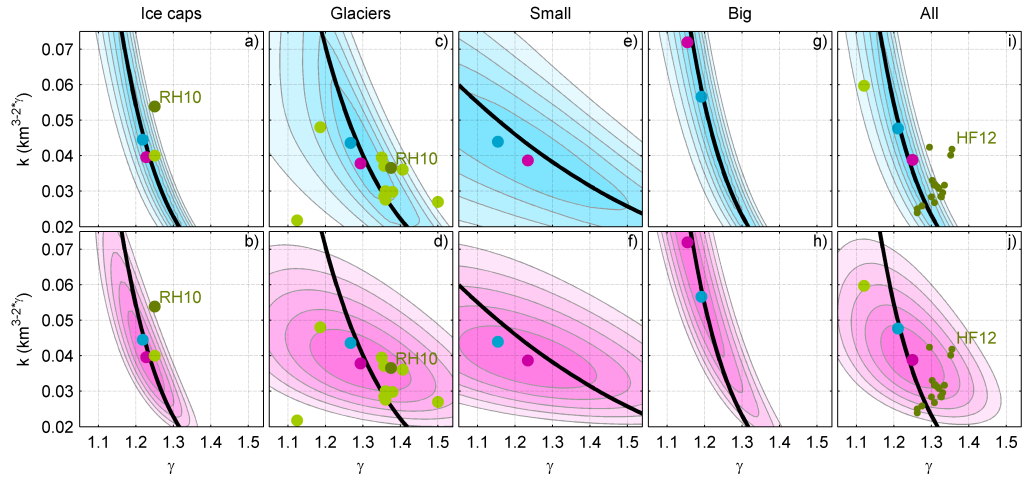

Radic & Hock (2010) use Chen & Ohmura’s (1990) glacier relationship of V=0.2055 * A1.36 but replace the exponent with 1.375 as theoretically argued by Bahr et al. 1997 (here A and V have units m2 and m3) . However, the units of the scaling-constant depends on the exponent. Thus the Chen and Ohmura constant simply does not apply for an exponent of 1.375. To illustrate the problem then consider this: First express Chen and Ohmura in km2 and km3 units: V=0.029704 * A1.36. Then follow RH2010 and replace the exponent with 1.375. If we apply the resulting scaling law to a large 500 km2 glacier then we get V= 153 km3 when we start from km-units, but V=188 km3 if we had started from m-units as in RH10. -and we would get V=139 km3 if we had used Chen&Ohmura’s γ=1.36. I believe this to be the origin of the positive bias in Radic and** ****Hock (2010)**. I discuss this further in my paper, and also show how well other scaling relationships match the total volume in the volume database (see fig3c&d, reproduced here).

The solid black curves show the combinations of exponents and constants that result in exactly the same total volume as in the volume database. We see that RH10 falls a good distance above the line, which indicates that it results in a too large total volume (total volume scales 1:1 with k for a given γ). The original Chen & Ohmura relationship (k=0.029, γ=1.36) on the other hand falls very close to the line.

New physical methods

Huss & Farinotti has also very recently estimated global glacier volume (~43cm) using a truly innovative flux conservation approach. In this approach it is necessary to assume both surface mass balance and a calving flux. This approach has the great advantage that it results in ice thickness grids for every glacier in the world, and thus allows for a much more detailed validation of the results. It can also be used as the starting point in more physical models of glacier mass loss. The individual volume estimates are probably mostly better than the scaling based volume for individual glaciers. However, that does not mean that the total volume also will be better if there is a bias. And that is a real concern because the parameterisations have been calibrated on rather small empirical datasets. I am also concerned about the potential for bias on the largest glaciers and ice caps. So that is why I think that more statistical approaches like mine remain important.

A good overview of different methods for volume estimation can be found in the introduction to Linsbauer et al. 2012.

Area-Volume scaling and slope.

I have since become aware that volume-area scaling apparently is controversial, and the main arguments seem to be three-fold:

- Volume is obviously not independent of area as V=A*H. Part of the correlation between A and V is thus trivial. It is therefore argued that the correlation appears more impressive than it really is. This has lead to a mantra that it is somehow wrong to plot area against volume. In my opinion it is not. Such plots show that volume and area correlates - it simply does not matter whether the correlation is trivial or not. You can clearly predict volume from area, and that is what such a plot shows. Ofcourse you should not be overly impressed by a high R2 value, and you should be careful how you do the statistics in general in such a case. In the case of my own paper it would make absolutely no difference to the total volume estimate, nor to the percentage deviation from the fitted line whether I plotted thickness or volume on the y-axis in figure 2.

- There are no measurements of volume, only measurements of thickness which are then inter/extrapolated to the entire glacier. I agree. However, the scatter in area volume plots (the deviation from a straight line) is much greater than the plausible level of uncertainty in the volume estimates. The dominant source of the scatter is simply the fact that area and volume is never perfectly correlated. The uncertainty in the scaling regressions is primarily coming from this real scatter in the data, to the point of the measurement uncertainty having a neglible influence. Even with perfect measurements of area and volume the scatter would still be there. So in short i think this “no volume measurements” critique is misplaced as its effect on the total volume estimate will be very minor.

- Ice physics dictate that ice velocities increase as the slope increases. Thus a thinner glacier can accomodate the same mass flux when the slope is steeper (see e.g. Haeberli and Hoelzle 1995, or text books such as Paterson). We thus expect slope to be important for the thickness and thus volume. This has led some people to conclude that “slope must be included in volume estimates”. It is true that this will lead to better estimates of the volume of individual glaciers, but that does not mean that you need to include it or even that it leads to better estimates when you estimate the total volume of hundreds of thousands of glaciers. Indeed you could even choose to estimate global glacier volume statistically like this: Vtot=avg_thickness*Areatot, even if it is poor at capturing the volume of individual glaciers well. The only problem being how you would go about estimating the average thickness of all glaciers in the world. The best argument I have against the “slope must be included” argument, is a test where I show that plain volume area scaling performs well against global model data where slope effects are included. This demonstrates that there is no reason, to the best of our physical understanding, to expect that volume area scaling would not work in the real world.

- Please note that my statistical model actually does allow for slope to be taken into account, but only does so if it leads to an actual improvement in the performance in a validation against withheld data. It does so because R, L and A are predictors and mean slope can be calculated as R/L or alternatively R/sqrt(A). From ice physical considerations you have an expectation for which exponent the slope should have in the thickness(/volume) relationship. However, there are many reasons why nature might deviate from the theoretically derived relationship. One reason could be that the thermal regime, and thus the ice mechanical properties are related to vertical range (think of temperature lapse rate). Indeed, Haeberli and Hoelzle (1995) uses vertical range in their parameterisation of basal shear stress. Personally, I believe that continentality also plays a strong role in the thermal regime, and should be included in the basal shear stress parameterisation. For that reason I think you have to be careful if you are going to extrapolate a basal shear stress parameterisation calibrated on continental glaciers to maritime environments. Neglecting this effect could lead to a bias in the total volume. I am not arguing that my own estimate is without bias, rather I am arguing against the attitude that there is only one way of doing this and that all other methods are wrong.